199. The Ghost and Mrs. Muir

Posted: August 22, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Bernard Hermann, Charles Lang, Dorothy Spencer, Gene Tierney, George Sanders, Joseph Mankeiwicz, Philip Dunne, Rex Harrison, The Ghost and Mrs. Muir Leave a comment

Jump to the trailer. Seriously, it’s kind of hilarious in the v.o. department, though perhaps not quite as hilariously horrid as that poster. Obviously, the studio was afraid that no one would bother to see Gene Tierney if she wasn’t sexing it up.

The 1001 Book Why: “Philip Dunne’s urbane script…Charles Lang’s translucent cinematography, and one of Bernard Hermann’s gentlest and most lyrical scores.” — Philip Kemp

The Haiku:

If I met a ghost

Who talked like Rex Harrison

I’d fall in love, too.

The Cinema 1001 Take: As I write this (August 2013), the latest 1001 edition is about to be released, and I truly expected this movie to be on the chopping block. Having not seen it, I thought it had to be some dopey rom-com. Just a few minutes in, I saw the error of my ways. This Ghost should be safe from any cuts. It’s wonderful.

It’s a fine case where list context alters the lens through which you view a movie. Just a few movies back at number 191, A Matter of Life and Death acknowledged the fact that wars kill people. In its own quiet way, Ghost does the same; Mrs. Muir is a young and lovely widow. It’s better that we don’t know the cause; there were plenty of women who could relate to her.

It IS a bit of a shock to see Gene Tierney done up in Gibson Girl high neck and long skirt, and early on you may wonder if she’s going to pull the whole period thing off. But once Rex Harrison enters, you’ll relax. He and Tierney have a fine chemistry together; because he doesn’t get all swoony over her looks (unlike every single cast member in Laura), we can look past them and get engaged in the story.

It’s easily one of the finest hours of Philip Dunne, a man who seemed fairly immune to off days. In fact, the whole team is crack: Hermann and Lang as mentioned above, the great Dorothy Spencer on the Movieola, and Joseph Manciewicz finally breaking out after a bit of a herky-jerky start as a director. Harrison is brilliant from his first appearance, and Tierney gets better and better as the film goes on, with George Sanders purring like a big creepy cat to add a suave seediness to the proceedings.

In fact, the movie has a nearly Continental sophistication in the way it handles a perfect storm of romantic entanglement, as well as potentially very gooey sentiment. The ghost, jealous to distraction over Tierney’s falling hard for the flesh-and-blood Sanders, comes to his senses in one of the loveliest and noblest speeches ever filmed; it made my 17-year-old son tear up (I myself was a bit of a mess as well). Once Tierney realizes that what everyone else has predicted about Sanders is true, there is no pat resolution. When next we see her, the elegant fashions of the aughts have been traded for the sturdy and dowdy civilian gear of WWI. Tierney and Harrison both are forced to make choices, neither of which are easy, but which are right—and that pay off in an exquisite and sweet ending.

The fact that it never feels sentimental or pandering—quite unlike the silly sit-com of the same name in the late 60s—is a tribute to the tremendous grace of the filmmakers and actors. The Oscars ignored it. But audiences weary of war must have found it a light and delicate balm for their grieving hearts.

198. Out of the Past

Posted: August 22, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Build My Gallows High, Cinema 1001, Daniel Mainwaring, greatest noir, Jacques Tourneur, Jane Greer, Kirk Douglas, Nicolas Musaraca, Out of the Past, Robert Mitchum, Roger Ebert, Roy Webb, sexy cigarettes Leave a commentThe 1001 Book Why: Tom Gunning says it “may be the masterpiece of film noir…leaves us with the enigmas of fatal desires, the ambiguities of loves laced with fear.”

How to See It: Watch it on Amazon Instant for 10 bucks.

The Haiku:

Robert Mitchum’s eyes

Cigarette delirium

The best noir. Bar none.

The Cinema 1001 Take: It starts with a long shot from the driver’s seat, and could be any number of movies from the decade. Then the name Jacques Tourneur appears onscreen. If you can keep the smile off your face, you haven’t watched enough Tourneur.

Out of the Past represents the great director’s graduation to the A list. And yet, much of its greatness is that it still feels cheap in exactly the right way, as good noir should. Tourneur had been forced to rely on story, lighting, and tight framing to make the most of his four-dollar budgets, he continues to use them now. Many directors who created good movies on a dime—Tim Burton and John Carpenter come to mind—lose their meaning when they get enough money to relax, and in fact Burton’s best work remains the movies with the smallest budgets. Tourneur takes them all to school by sticking to the textbook he wrote on Cat People and I Walked with a Zombie.

The casting plays a huge part in what makes the movie tick, and it’s particularly interesting to watch after the bigger budget but icier Gilda. Kirk Douglas had only been in one other movie; Robert Mitchum had only been in one significant one, Crossfire. Jane Greer might as well have not been in any. You can feel the energy of new talent here, every one of them digging in with the appetite of those chomping at the bit to break out unmemorable movies and into something decent. This one would make the men stars. Oddly, given his spectacular turn as a charming and deadly viper here, Douglas would flip quickly into jolly leading men, parts that never suited him as well as villains. Watching Douglas père and his flinty eyes that never miss a trick, you can practically see the DNA code being written that will spawn Gordon Gekko in the next generation. Mitchum’s eyes tell a different story altogether, one of a world weariness that nothing can cure; no noir hero ever proved quite so tough to fathom or so devastatingly sexy. Only Jane Greer didn’t quite take. And yet, it’s her very B movieness that makes her so wonderful. She’s a diamond that can never be quite free of its carbon crust, that will never quite fit in an expensive setting. She’s perfect, but doomed, in and out of the movie.

Daniel Mainwaring, an old but undistinguished-to-this-point Hollywood hand, adapted his own novel with the marvelous title Build My Gallows High. It’s taut and tough, with an ambiguity rare to Hollywood, nicely summed up in the 1001 book—including the last moment, which I shan’t spoil here. Tourneur reteamed with two Cat People alum: the great d.p. Nicolas Musuraca (also of the Val Lewton-produced haunter The Seventh Victim) for the rich textured photography, and Roy Webb, who created another lovely score.

Roger Ebert calls it “The greatest cigarette-smoking movie of all time…There were guns in Out of the Past, but the real hostility came when Robert Mitchum and Kirk Douglas smoked at each other.” (Read more over at my source, a wiki citing Ebert’s 200 Cigarettes). One might also add that their chin dimples compete. But no need to add farce to a movie that doesn’t take itself too seriously as it leaves a little dent in your heart. Somehow, Tourneur pulled off elegant and tawdry at the same time and created perfection.

197. Monsieur Verdoux

Posted: August 10, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: 1001 Movies, Charlie Chaplin, Cinema 1001, Marilyn Nash, Martha Raye, Monsieur Verdoux Leave a commentThe 1001 Book Why: “One of [Chaplin’s] most tightly constructed narratives, which he unselfconsciously considered ‘the cleverest and most brilliant film of my career’ “—David Robinson

How to Watch: Volume 2 of the Charlie Chaplin Collection features this one as well as City Lights, and the interesting, lesser-known works A King in New York and A Woman in Paris. There’s a good quick introduction to the movie by none other than David Robinson (see above); it includes interesting contextual info on the political environment, the story’s factual and Wellesian origins, and budget constraints. There’s also a documentary within the Collection that briefly touches on the movie.

The Haiku:

Serial killer

Tries but fails with Martha Raye.

Darn. Maybe next time.

The Cinema 1001 Take: There’s a bitter edge to Monsieur Verdoux right from the opening, in which a dysfunctional, bickering family straight out of a W.C. Fields comedy snarls and bitches at each other. The acting here, as in much in the film, is old-fashioned, big and declamatory, almost as if the actors are holding for laughs. So when Chaplin finally appears, after using the time-honored theatrical technique of delaying his protagonist’s entrance, it’s like seeing a longlost friend: the moué, the raised eyebrows, the devilish sparkle in the eyes as he rifles through a stack of bills with lightning precision.

It’s a master class in comedic acting. But it’s from and possibly for another time. Capra, Sturges, Huston, and most of the American directors of the period had already tapped into a naturalism that more accurately reflected the messiness of life. With few exceptions—Chaplin’s onscreen wife and son (Mady Cornell and Allison Roddan) and Marilyn Nash, about whom more below—everyone here is playing to the cheap seats. Casting Martha Raye is either genius or lunacy; she doesn’t act, just sort of bellers, her eyes flat as a shark’s. She does have a surprisingly great body, and lots of natty skirt suits to highlight the fact. Either way, some of her scenes with Chaplin are brilliantly funny, but you may feel weary afterward; this is comedy of will and effort, not joy.

Of course, that’s to be expected given the doghouse in which Chaplin had unwillingly taken up current residence. Scandals, lawsuits, and exile to Europe were all tied up in one big head and heartache package, and the toll shows. Toward the end, Monsieur Verdoux states simply from the witness stand that to kill one or two makes one a murderer but to kill thousands makes one a hero. It’s an observation difficult to argue with, yet there’s a whiff of angry victim to it. As (spoiler) Verdoux is led off to face death, his posture erect, his step jaunty but for a slight limp (I can’t find anything written about this online, so don’t know if it’s characterization or real), he doesn’t seem particularly tragic. He’s just a guy who didn’t get that killing is as wrong on a small scale as on a big one, the world’s reaction be damned.

And yet, Chaplin can’t fully suppress his inner optimism. The best bit in the movie takes place when Verdoux picks up a girl on the street, Marilyn Nash, mentioned above; she has just “been released from prison” in order to get around the censors’ objections to implied prostitution. Nash is lovely and natural, and would leave the big screen after just one more picture to become a casting director. Chaplin composed the movie’s score, and, at one point, when Verdoux is moved enough by the girl’s plight that he decides not to use experimental poison on her, the strings swell into the first few notes of “Smile.” Under the anger and disappointment, Chaplin was still a sucker for the joy of a pretty face, and the beauty of people being kind to each other.

196. Gilda

Posted: August 6, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a commentThe 1001 Book Why: Kim Neuman says, “[Glenn] Ford and [Rita] Hayworth, limited but engaging and photogenic actors, have definitive performances drawn out of them like teeth.” My!

How to Watch: The Columbia Classics edition is about your only choice, and features a brief and breathless video bio of Rita Hayworth.

The Haiku:

Put the blame on Mame.

Rita Hayworth flips her hair.

Feel yourself shiver.

The Cinema 1001 Take: By this time, if you’re watching these things in order, you’ve seen a LOT of noir. So if the opening feels a little BTDT, don’t be surprised. The solid if unremarkable Charles Vidor (unrelated to the great King) hits his marks and no more on this one, but he’s assisted by a somewhat better-than-average script by Jo Eisinger and E.A. Ellington with plenty of nondescript but exotic Latin American intrigue, and gives a standard femme fatale a snazzy soundtrack as she leads the poor sap down the road to ruin.

But let’s face it: This is Rita Hayworth’s movie—or rather, this is the movie where Rita Hayworth is exploited to the utmost extent, what with Rudolph Maté’s camera ogling her like a Tex Avery wolf and Jack Cole putting her through dance steps that make her endless legs look even longer. It’s borderline creepy, especially if you’re familiar with any of the details of Hayworth’s tragic childhood and adolescence, which came to light after her death. The steel in Hayworth’s eyes is real, from her 1001 list debut in Only Angels Have Wings to here.

In fact, the movie’s loveliest moment is its quietest, and the one time it seems to let the star stop selling sex like a peepshow barker in Times Square circa 1978. Late one night, Hayworth sits on a kitchen table, “singing” as she “plays” a guitar “Put the Blame on Mame,” a number that’s sweetly sad in this setting, only to become ridiculously over the top when Gilda goes all Gypsy Rose Lee in a nightclub. It’s not her real voice, despite a longstanding rumor to the contrary; Anita Ellis dubs the voice here, but Hayworth lip syncs like the pro that she is. But it’s no less sweet for that.

Without Hayworth, it’s hard to imagine anyone ever blinking an eye over Gilda. Glenn Ford is serviceable, and plays a jerk; it’s the rare movie that’s pretty equally balanced in its misanthropy and misogyny, but there’s really no one here to like. There’s a shootout that calls to mind the nightclub scene in DePalma’s Scarface remake (you know, where the guy in that disturbing giant head dances around and gets pumped full of lead). Reconsider Gilda after watching the creme de la noir in two clicks, and you’ll see the difference between a by-the-numbers big-budget cash cow and a black beauty that gleams all the more brilliantly for its humble setting. Then again, Hayworth is so pretty, you may just want to indulge the Tex Avery wolf in yourself. Burn her wild auburn hair into your memory; it’ll all be gone next time we see her.

195. It’s a Wonderful Life

Posted: July 27, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: angels earning wings, Donna Reed, Frank Capra, Henry Travers, It's a Wonderful Life, Jimmy Stewart Leave a commentThe 1001 Book Why: Karen Krizanovich says, “Capra’s first postwar film revels unashamedly in the goodness of ordinary folks as well as the value of humble dreams, even if they don’t come true.” She also notes that it is actually more a “delightfully shrewd screwball comedy packed with fast, incisive observations on love, sex, and society.” If that first bit and the trailer above are scaring you away, please read the 1001 Take below!

How to Watch: Preferably in a theater with a full house, but this version on DVD is the one for home viewing. BEWARE COLORIZATION!! Both Capra and James Stewart rightly had kittens when the ghastly process claimed this movie as one its early victims. You can also watch full versions on YouTube provided you don’t mind subtitles in Spanish or Russian.

The Haiku:

My son, age 15,

Said, “It’s like the most bad-ass

Twilight Zone ever.”

The Cinema 1001 Take: If you avoid this one like a mall Santa due to the endless repeats at Christmas, you can hardly be blamed. That hokey beginning, featuring a fetus-like blob in a black starry sky that is presumably the voice of the Almighty, doesn’t help matters much. Neither does the focus on the bumbling angel Clarence (Henry Travers) and the uber-corny concept of earning wings. Press beyond your biases, I beg you.

The best thing about James Stewart working with Frank Capra is that Capra knew how to tap into Stewart’s dramatic capability. In both Wonderful Life and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Stewart breaks big. He’s unafraid to show his fallibility, his despair, and his sorrow as he watches his dreams not just die, but be utterly crushed. I cannot find the source (I thought it was David Thomson, but it isn’t in any of my books), but someone observed that George Bailey’s agreement to give up everything he cares about to marry Donna Reed is one of the most furious proposals in history. It’s that raging against the machine wherein Life‘s true greatness lies.

Capra’s balance is surprisingly delicate, which is why the worst possible way to watch his movies is on TV with commercial interruption. Life starts with an average childhood of the time, complete with physical abuse, leading, naturally, to a young man who desperately wants to flee his crappy small-town existence. That restlessness and unexpressed mourning for what might have been never leaves Stewart’s dark eyes; neither does Donna Reed (unexpectedly sexy and good if your primary recollection of her is from that perky TV show) ever look complacent; there’s an uneasiness in her portrayal. Her character is fully aware that her husband lives a life of compromise and regret.

Due in large part to the way that his movies have been chopped to fit the small screen and make way for plenty of commercials, history has turned Capra’s legacy into one of You Betcha Americana. He’s so much more realistic than that. His optimism fully acknowledges the darkness and ambiguity of human nature, but it also celebrates the average man and woman not for being just good folks but for making difficult, brave choices. The sweet moments in Wonderful Life stem from people drawing on their basic goodness to overcome bad ideas and decisions; it’s grassroots-level power, common decency, and horse sense, not an angel, that save George Bailey and his family.

I saw the movie on December 23, the day my father died, with my son, who really did make the comment above. This fully wired video-game obsessed kid was completely caught up in the movie, and still mentions it months later. Forever, the movie will unite my son, the last of five grandsons and sole namesake, with my dad. It is a wonderful life, even when it sucks sometimes. And movies make it better.

194. Black Narcissus

Posted: July 25, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Alfred Junge, Black Narcissus, Deborah Kerr, Emeric Pressburger, Hein Heckroth, Jean Simmons, Kathleen Byron, May Hallatt, Michael Powell, Reginald Mills, repressed nuns, Rumer Godden, snail jewelry Leave a comment

The 1001 Book Why: According to Kim Neuman, “a matter-of-fact account of the failings of empire….the studio-bound exotica glowing under Jack Cardiff’s vivid technicolor cinematography.” He also mentions the “jeweled snail” on Jean Simmons’ nose. Heh.

How to Watch: Jump to Criterion’s gorgeous transfer of the movie in its entirety on YouTube.

Book Error: The movie did not premiere in the UK until 1947; the book has the movie listed under 1946, when The Archers were busy with A Matter of Life and Death (and Michael Powell was, presumably, getting busy with Kathleen Byron, pictured above).

The Haiku:

Powell/Pressburger

Himalayan nun freak-out

With Sexy Results!

The Cinema 1001 Take: This movie is really, really pretty. It’s also beautiful, but the first adjective emphasizes the candy store delight that Powell & Pressburger managed to squeeze out of Pinewood Studios; it’s somewhat revelatory to learn that the movie was not shot on location, but mostly at Pinewood and at the home of a retired Indian army officer. The towering Hindu Kush range in the background is either a matte shot or mountains painted on glass. (Disney had used this same trick to provide visual depth to the scenery of his animated features.)

It’s a bit of an odd story, and subtler than you think, given the lurid promise of Nuns Running Amok. Rumer Godden, the novelist who provided the source material, wrote about nuns and India, sometimes separately but here in the same book. The mountain setting weaves a spell with delicate threads, but the sheer quantity of sensory input becomes an inescapable trap for the unsuspecting and ill-equipped British sisters.

It’s also the first time Michael Powell goes head-to-head with the issue of repressed desire, which will increasingly inform his movies to come. He also finds a new redhead to fixate on; Hitchcock loved his icy blondes, but Powell was all about the fire. If you’ve seen A Matter of Life and Death, you’ll recognize lovely Kathleen Byron, playing the nun most likely to flip out. (You may feel you recognize her even if you haven’t seen the other movie, as she’s a dead ringer for Tilda Swinton.) Offscreen, Byron had replaced her co-star Deborah Kerr as Powell’s love interest, and, as a good director should, exploited the tension between the two beauties. In the spookiest scene, Byron whips off her habit, dons a cheap dress, and scrawls blood-red lipstick across her mouth. It’s super creepy.

But don’t make the mistake, like I did the first time I watched the movie, of setting yourself up to be as strung-out as the nuns eventually get. For all its horror elements and weirdness, Black Narcissus insinuates rather than injects its way under your skin. Its one truly baroque element, May Hallatt’s mad-cow-in-a-china-shop performance, threatens to derail the film before it can really get going; the performance belongs in slapstick, not here, and it’s distracting in its wrongness. And in the end, the movie is less the religious critique that many will desire than a graceful admission that colonialism sucks. India was about to claim independence; in the Criterion notes, Dave Kehr calls the ending “a respectful, rational retreat from something that England never owned and never understood,” though frankly, the only ones the British ever treated respectfully were themselves. I mean, that’s pretty much how colonialism works.

Other than Hallatt and Jean Simmons—that snail and the dark pancake make-up are pretty distracting—the acting is terrific, particularly from Kerr, Byron, and sexy David Farrar. Designers Alfred Junge (production) and Hein Heckroth (costumes) are on point as always, Reginald Mills edits with ease, and Cardiff performs his usual camera wizardry; he and Junge both won Oscars for their work in the movie. Soak, don’t jump, into this lush beauty.

193. Notorious

Posted: July 24, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Alfred Hitchcock, Ben Hecht, Cary Grant, David O. Selznick, Duel in the Sun, Edith Head, Gregg Toland, Ingrid Bergman, Notorious, Robert Capa, Rosselini, Ted Tetzlaff Leave a commentThe 1001 Book Why: Kim Neuman states that the “intense triangle drama constantly forces you to change your feelings about the three leads,” and lauds the “sumptuous romance” that includes “at that point, the screen’s longest close-up kiss.”

How to Watch: The Criterion edition looks gorgeous and has tons of extras, including source material and a radio broadcast of the story with Ingrid Bergman and Joseph Cotten.

The Haiku:

Ingrid: dark angel

Grant: a devil named Devlin

Hitchcock: magician

The Cinema 1001 Take: Hitchcock had collaborated with his first great crush, Ingrid Bergman, before, in Spellbound. David O. Selznick had screwed that up, by cutting the hell out of the dream sequence and insisting that his therapist be brought on as a technical advisor.

Hitch had also collaborated with his best leading man, Cary Grant, before, in Suspicion; Selznick had screwed that up, too, by destroying Hitch’s original unhappy ending.

How much the great producer would have sunk Notorious, we’ll never know. He did push hard for the unavailable Joseph Cotten instead, citing Grant’s “difficulty,” which seems to have really meant “high price tag.” Certainly, Cotten was terrific in his earlier work with Hitch, Shadow of a Doubt, but his screen chemistry with Bergman would prove dismal in the star-crossed Under Capricorn a few years later. In any event, an unexpected blessing to everyone but Selznick intervened: Duel in the Sun, which he seemed to think would be “Gone with the Wind II” and which everyone else called “Lust in the Dust” for years, featured his squeeze Jennifer Jones, who, like Selznick, was still married to someone else. The naturally fraught production consumed him, and he sold Notorious to RKO, resulting in a filmmaking team high on the sweet wind of freedom.

They created a masterpiece. Hitch and Hecht worked on the script and it’s lean and not too clean, with a rare ambiguity for Hollywood. And there’s a new kind of suspense; where Hitchcock used nerves and bombs in earlier movies (Blackmail, Sabotage), he here uses betrayal, distrust, and bitterness to keep the audience breathless. When Grant is forced into pimping out Bergman in the name of duty, the two convey more agony with silent glances than a decade of 70s method actors gnashing their teeth and bellowing.

Ted Tetziaff’s cinematography works nicely; the Hollywood vet and Carole Lombard favorite also shot My Man Godfrey. Following this picture, he’d become a director, with the noir pic The Window his most famous work. (Uncredited cameramen Gregg Toland and Robert Capa certainly helped.) Edith Head makes sure that everyone is dressed to, well, kill, and Theron Warth’s editing makes it all sing.

The whole thing is about as close as it gets to perfect. Arguably, there’s a tenderness here that Hitchcock would never again display. He’d make one more movie with Bergman, the experimental failure Under Capricorn; during and after, Bergman would “betray” everyone by running off to be with Roberto Rossellini. It would take Hitch five years to find another gorgeous blonde to crush on, and Grace Kelly never had the warmth or talent of Bergman. All the right things fell in place for Notorious, a rare and pure cinematic gem.

192. Great Expectations

Posted: July 23, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Alec Guinness, Alfred Junge, Bob Cracker, Cinema 1001, David Lean, Finlay Currie, Great Expectations, Guy Green, In Which We Serve, Jean Simmons, John Mills, Martita Hunt Leave a comment

The 1001 Book Why: Karen Krizanovich deems it “the finest literary adaptation ever filmed, as well as one of the best British films ever made,” and cites Oscars for Best Art Direction and BW Cinematography, with noms for Picture, Director, and Adapted Screenplay.

Where to Watch: Jump to the movie in its entirety on YouTube.

The Haiku:

Old Miss Havisham

Rasps out, “A great bride cake. Mine!”

Creepy delicious.

The 1001 Take: Seven of the BFI’s top 100 British films of all time are David Lean’s, more than any other director; this one is number five. But contrary to what many people think based on his later work, Lean is not necessarily about Technicolor spectacle sweeping across massive locations. Four of the seven movies are black and white beauties, and it’s hard to imagine his two Dickens-based works shot any other way.

It’s also hard to imagine anyone doing Dickens better within the confines of a two-hour feature; the multi-hour Nicholas Nickleby on stage and TV and the wonderful musical The Mystery of Edwin Drood pass muster, but they’re different formats. According to an interview conducted by the AFI (and contained in Conversations with the Great Moviemakers of Hollywood’s Golden Age, edited by George Stevens, Jr. source of all quotes contained here), Lean was initially daunted by the material and hired novelist Clement Dane, a “sort of” Dickens expert. “I think the thing not to try to do is a little bit of every scene in a novel, because it’s going to end up a mess,” he states. Dane’s screenplay did exactly that, and was rejected. Lean “got the book and quite blatantly wrote down the scenes that I thought would look wonderful on screen.”

The result is stunning, and the opening may be the most beautiful horror movie ever shot, as a child races under gibbets, empty ropes swinging, to a cemetery. There, young Pip (Anthony Wager) encounters the fierce Magwitch (Finlay Currie). Then things crank up to genius level when we enter the crumbling mansion belonging to Miss Havisham (Martita Hunt) and her protégé Estelle (Jean Simmons, a startling beauty), played by Martita Hunt. In this first act particularly, the casting is spectacular and so are the actors.

That Act II feels a bit of a letdown may be inevitable—and yet, its moderate tempo may be a needed respite given the speed and intensity of Act I, which will be back for Act III. John Mills was famously criticized as being too old—a 38-year-old playing 20-year-old Pip. While he’s solid and certainly less distracting than the AARP candidates in Grease, he and Valerie Hobson (grown-up Estelle) aren’t nearly as captivating as their younger counterparts. What energy there is stems from the one child, skinny John Forrest, who grows up to be Alec Guinness as Herbert Pocket. Lean said that Guinness was a nervous wreck in this, his first speaking role; the director would tell the actor that they were just rehearsing and roll film without Guinness knowing. To hear them tell it, neither was very fond of the other and they argued constantly. And yet Guinness kept coming back, and Lean kept getting spectacular work out of him in a partnership over five films, one of which would land Guinnes the Best Actor Oscar (Kwai).

With the return of Currie in the last third, and Hunt soon after, the movie starts clipping along again at its original pace; Dickens’ adaptations have to move fast to keep viewers from getting mired in the handy coincidences that drive them, and Lean knows it. The ending leaves you satisfied, and the overall experience is immersive, and feels like a thorough dunking in Dickens even with all the liberties taken. Lean would do a follow-up with Oliver Twist a few years later, Green behind the camera once again, and that version remains the best of the many attempts to condense that story into a performance.

Much of what makes GE work is its deep, dark, mysterious feel and the beautiful work of Guy Green, who had, up to that point, worked as a camera operator on the Lean film In Which We Serve. Lean had begun photography with Bob Cracker, but Lean claimed “it was almost the same as Brief Encounter, very real-looking.” He wanted “much more daring. Huge, great black shadows. Great big highlights over the top, because it’s Dickens.” Green stepped in and ended up winning the b/w cinematography Oscar for the year. The ghostly gray melts into black. In Miss Havisham’s, the atmosphere seems so tangible that you may have a physical reaction, reaching up to brush cobwebs out of your hair or grab for your stomach as rats scurry over the huge cake encrusted with mold.

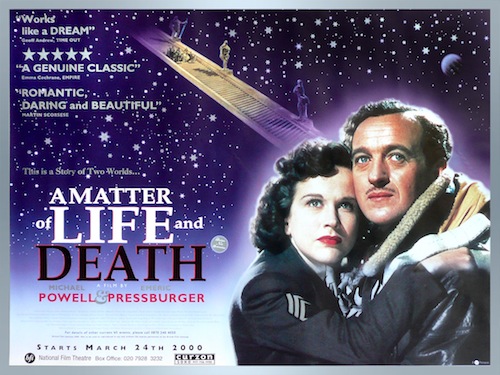

191. A Matter of Life and Death

Posted: July 22, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: A Matter of Life and Death, Alfred Junge, David Niven, Defending Your Life, Emeric Pressburger, Heaven Can Wait, It's a Wonderful Life, Jack Cardiff, Karen Krizanovich, Kim Hunter, Marius Goring, Michael Powell, posthumous reprieve, Reginald Mills, Stairway to Heaven, The Archers Leave a commentJump from this link to watch the movie in its entirety on YouTube.

The 1001 Book Why: Karen Krizanovich calls it “a lasting tale of romance and human goodness that is both visually exciting and verbally amusing,” and also gives a lot of love to Alfred Junge’s set design.

Where to Watch: YouTube, linked above.

The Haiku:

Long escalators.

Heaven’s a bureaucracy.

You might as well live.

The Cinema 1001 Take: The 1001 editors do love The Archers, aka Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, giving them two shoutouts in 1946 alone (Black Narcissus is on deck). It’s a delight. No one does intelligent romance like P&P.

As noted in the 1001 book and in any discussion of the movie, Matter was conceived as a propaganda film to ease strained relations between Britain and America post WWII. I didn’t know there were strained relations, but the Brits were not thrilled over America’s late entry into a war that had crushed the hell out of their country. Rather than focus on an American serviceman having his way with an English rose before disappearing, Matter flips the roles, beginning with a marvelous scene in which a British pilot (David Niven) leaps from his airplane, preferring that to literally going down in flames, as a helpless WAC (Kim Hunter) tries to talk him through it. (If this scene doesn’t call September 11 to mind, you must not be old enough to remember that day in 2001.)

From there, we’re transported to the terrifyingly efficient bureaucracy that is the movie’s Heaven—a grim place that nonetheless points up the distinction between Americans and Brits with fine humor. In a rare glitch, a death has been botched. Niven’s character is alive, in love with Hunter’s character, and louche angel Marius Goring has to un-botch if possible.

The idea of getting a posthumous reprieve was not new, of course; the first Heaven Can Wait had been made in 1943, and the concept is still popular today (Albert Brooks’ Defending Your Life is a relatively recent example). But this movie, and It’s a Wonderful Life (which would be released in the states within a month of Matter‘s British premiere) are both decidedly darker. It’s only natural that, with the boys safely, if not always soundly, home, what-if speculation would occur.

But unlike Wonderful Life, the reverence for celestial beings is absent from Matter. In fact, the point of view leans decidedly toward Niven’s character simply hallucinating as result of brain trauma as opposed to any actual intervention, a nice humanistic touch in contrast with the cosmic silliness of Wonderful Life‘s opening and closing bits. “We are starved for Technicolor in heaven,” quips Goring, as he witnesses the gray rose on his lapel morphing to a glorious pink. Indeed, the technical artistry and experimentation of Matter is one of the primary reasons to watch it. It’s hard to imagine an American director embracing a vision of Heaven as a monochromatic, rank and file/black and white environment with stairways straight out of Escher, as opposed to the vibrant richness of earth. No wonder Niven fights so hard to stick around. (The Archers were not pleased with the American retitling of “Stairway to Heaven,” but the original title was deemed too grim for Yanks.)

Jack Cardiff’s masterly cinematography and ease in both color formats does justice to Junge’s production design, and Reginald Mills’ editing—including incorporating freeze frames with motion, as well as b/w-to-color transitions—is seamless. Above all—or rather, beneath—is the superb writing of Powell and Pressburger. Yes, it’s formula, and yes, you know it will turn out all right; this is post WWII and no one wanted more heartbreak. But within that container, there’s suspense, wit, and agile, vigorous thinking that challenges without being abrasive. Anyone interested in filmmaking or good storytelling will benefit from studying The Archers, writers most of all.

190. The Killers

Posted: July 21, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Anthony Veiller, Ava Gardner, Burt Lancaster, Cinema 1001, Film Noir, Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Miklos Rosza, Quentin Tarantino, Robert Hilton, Robert Siodmak, The Killers 4 CommentsThe 1001 Book Why: Martin Rubin claims it’s superior noir, with a non-linear flashback that allows detective Edmund O’Brien to relive Burt Lancaster’s sexier life without suffering the consequences—just the vicarious thrill audiences get from watching crime movies.

How to Watch: The Criterion edition features the 1964 adaptation as well, and a bunch of cool extras, including an Andrei Tarkovsky student project that is a 19-minute version of the movie.

The Haiku:

Hemingway’s story

Rocks the first minutes so hard.

The rest is OK.

The Cinema 1001 Take: For those who take the side that Hemingway was a superb short story writer and a less satisfying (even lousy) novelist, The Killers provides strong evidence. The first twenty minutes of this movie, a faithful adaptation of the eponymous story, are so kickass, so scary, with two of the most frightening sociopathic criminals ever put on film—the suspense is painful. Surely every filmmaker who ever shot cold-blooded gangsters, particularly Scorsese and Coppola, has watched this a million times. It still feels completely modern, and it’s a gorgeous realization of one of Hemingway’s crystalline, hard-edged and brilliant stories.

And then….well, we’ve got another 80 minutes of screen time to fill.

The enigmatic beauty of the story—a guy simply waits until he’s violently killed—is lost when Hollywood, bless its heart, feels the need to explain why (and that, by the way, he kinda deserved it). Rubin’s points noted above—that the use of non-linear flashback and the meta aspect elevate the film somewhat—are well taken. But well-constructed and taut are hardly synonyms for the blow-the-bloody-doors-off greatness that is this movie’s beginning. The movie doesn’t plod, but chances of the explanation living up to that prologue are slim.

It’s Burt Lancaster’s debut and Ava Gardner’s breakout after 5 years of pretty girl tedium, and they’re both stunning to look at. The film was a critical and commercial hit, doubtless in no small part due to the two stars’ eye candy quotient, and it grabbed 3 Oscar noms, including director for Robert Siodmak, editing for Robert Hilton, adapted screenplay for Anthony Veiller, and the beautiful score by Miklos Rosza. It’s also one of those movies that film geeks revere. Watch it just in case you end up at a dinner party with Tarantino.