195. It’s a Wonderful Life

Posted: July 27, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: angels earning wings, Donna Reed, Frank Capra, Henry Travers, It's a Wonderful Life, Jimmy Stewart Leave a commentThe 1001 Book Why: Karen Krizanovich says, “Capra’s first postwar film revels unashamedly in the goodness of ordinary folks as well as the value of humble dreams, even if they don’t come true.” She also notes that it is actually more a “delightfully shrewd screwball comedy packed with fast, incisive observations on love, sex, and society.” If that first bit and the trailer above are scaring you away, please read the 1001 Take below!

How to Watch: Preferably in a theater with a full house, but this version on DVD is the one for home viewing. BEWARE COLORIZATION!! Both Capra and James Stewart rightly had kittens when the ghastly process claimed this movie as one its early victims. You can also watch full versions on YouTube provided you don’t mind subtitles in Spanish or Russian.

The Haiku:

My son, age 15,

Said, “It’s like the most bad-ass

Twilight Zone ever.”

The Cinema 1001 Take: If you avoid this one like a mall Santa due to the endless repeats at Christmas, you can hardly be blamed. That hokey beginning, featuring a fetus-like blob in a black starry sky that is presumably the voice of the Almighty, doesn’t help matters much. Neither does the focus on the bumbling angel Clarence (Henry Travers) and the uber-corny concept of earning wings. Press beyond your biases, I beg you.

The best thing about James Stewart working with Frank Capra is that Capra knew how to tap into Stewart’s dramatic capability. In both Wonderful Life and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Stewart breaks big. He’s unafraid to show his fallibility, his despair, and his sorrow as he watches his dreams not just die, but be utterly crushed. I cannot find the source (I thought it was David Thomson, but it isn’t in any of my books), but someone observed that George Bailey’s agreement to give up everything he cares about to marry Donna Reed is one of the most furious proposals in history. It’s that raging against the machine wherein Life‘s true greatness lies.

Capra’s balance is surprisingly delicate, which is why the worst possible way to watch his movies is on TV with commercial interruption. Life starts with an average childhood of the time, complete with physical abuse, leading, naturally, to a young man who desperately wants to flee his crappy small-town existence. That restlessness and unexpressed mourning for what might have been never leaves Stewart’s dark eyes; neither does Donna Reed (unexpectedly sexy and good if your primary recollection of her is from that perky TV show) ever look complacent; there’s an uneasiness in her portrayal. Her character is fully aware that her husband lives a life of compromise and regret.

Due in large part to the way that his movies have been chopped to fit the small screen and make way for plenty of commercials, history has turned Capra’s legacy into one of You Betcha Americana. He’s so much more realistic than that. His optimism fully acknowledges the darkness and ambiguity of human nature, but it also celebrates the average man and woman not for being just good folks but for making difficult, brave choices. The sweet moments in Wonderful Life stem from people drawing on their basic goodness to overcome bad ideas and decisions; it’s grassroots-level power, common decency, and horse sense, not an angel, that save George Bailey and his family.

I saw the movie on December 23, the day my father died, with my son, who really did make the comment above. This fully wired video-game obsessed kid was completely caught up in the movie, and still mentions it months later. Forever, the movie will unite my son, the last of five grandsons and sole namesake, with my dad. It is a wonderful life, even when it sucks sometimes. And movies make it better.

194. Black Narcissus

Posted: July 25, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Alfred Junge, Black Narcissus, Deborah Kerr, Emeric Pressburger, Hein Heckroth, Jean Simmons, Kathleen Byron, May Hallatt, Michael Powell, Reginald Mills, repressed nuns, Rumer Godden, snail jewelry Leave a comment

The 1001 Book Why: According to Kim Neuman, “a matter-of-fact account of the failings of empire….the studio-bound exotica glowing under Jack Cardiff’s vivid technicolor cinematography.” He also mentions the “jeweled snail” on Jean Simmons’ nose. Heh.

How to Watch: Jump to Criterion’s gorgeous transfer of the movie in its entirety on YouTube.

Book Error: The movie did not premiere in the UK until 1947; the book has the movie listed under 1946, when The Archers were busy with A Matter of Life and Death (and Michael Powell was, presumably, getting busy with Kathleen Byron, pictured above).

The Haiku:

Powell/Pressburger

Himalayan nun freak-out

With Sexy Results!

The Cinema 1001 Take: This movie is really, really pretty. It’s also beautiful, but the first adjective emphasizes the candy store delight that Powell & Pressburger managed to squeeze out of Pinewood Studios; it’s somewhat revelatory to learn that the movie was not shot on location, but mostly at Pinewood and at the home of a retired Indian army officer. The towering Hindu Kush range in the background is either a matte shot or mountains painted on glass. (Disney had used this same trick to provide visual depth to the scenery of his animated features.)

It’s a bit of an odd story, and subtler than you think, given the lurid promise of Nuns Running Amok. Rumer Godden, the novelist who provided the source material, wrote about nuns and India, sometimes separately but here in the same book. The mountain setting weaves a spell with delicate threads, but the sheer quantity of sensory input becomes an inescapable trap for the unsuspecting and ill-equipped British sisters.

It’s also the first time Michael Powell goes head-to-head with the issue of repressed desire, which will increasingly inform his movies to come. He also finds a new redhead to fixate on; Hitchcock loved his icy blondes, but Powell was all about the fire. If you’ve seen A Matter of Life and Death, you’ll recognize lovely Kathleen Byron, playing the nun most likely to flip out. (You may feel you recognize her even if you haven’t seen the other movie, as she’s a dead ringer for Tilda Swinton.) Offscreen, Byron had replaced her co-star Deborah Kerr as Powell’s love interest, and, as a good director should, exploited the tension between the two beauties. In the spookiest scene, Byron whips off her habit, dons a cheap dress, and scrawls blood-red lipstick across her mouth. It’s super creepy.

But don’t make the mistake, like I did the first time I watched the movie, of setting yourself up to be as strung-out as the nuns eventually get. For all its horror elements and weirdness, Black Narcissus insinuates rather than injects its way under your skin. Its one truly baroque element, May Hallatt’s mad-cow-in-a-china-shop performance, threatens to derail the film before it can really get going; the performance belongs in slapstick, not here, and it’s distracting in its wrongness. And in the end, the movie is less the religious critique that many will desire than a graceful admission that colonialism sucks. India was about to claim independence; in the Criterion notes, Dave Kehr calls the ending “a respectful, rational retreat from something that England never owned and never understood,” though frankly, the only ones the British ever treated respectfully were themselves. I mean, that’s pretty much how colonialism works.

Other than Hallatt and Jean Simmons—that snail and the dark pancake make-up are pretty distracting—the acting is terrific, particularly from Kerr, Byron, and sexy David Farrar. Designers Alfred Junge (production) and Hein Heckroth (costumes) are on point as always, Reginald Mills edits with ease, and Cardiff performs his usual camera wizardry; he and Junge both won Oscars for their work in the movie. Soak, don’t jump, into this lush beauty.

193. Notorious

Posted: July 24, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Alfred Hitchcock, Ben Hecht, Cary Grant, David O. Selznick, Duel in the Sun, Edith Head, Gregg Toland, Ingrid Bergman, Notorious, Robert Capa, Rosselini, Ted Tetzlaff Leave a commentThe 1001 Book Why: Kim Neuman states that the “intense triangle drama constantly forces you to change your feelings about the three leads,” and lauds the “sumptuous romance” that includes “at that point, the screen’s longest close-up kiss.”

How to Watch: The Criterion edition looks gorgeous and has tons of extras, including source material and a radio broadcast of the story with Ingrid Bergman and Joseph Cotten.

The Haiku:

Ingrid: dark angel

Grant: a devil named Devlin

Hitchcock: magician

The Cinema 1001 Take: Hitchcock had collaborated with his first great crush, Ingrid Bergman, before, in Spellbound. David O. Selznick had screwed that up, by cutting the hell out of the dream sequence and insisting that his therapist be brought on as a technical advisor.

Hitch had also collaborated with his best leading man, Cary Grant, before, in Suspicion; Selznick had screwed that up, too, by destroying Hitch’s original unhappy ending.

How much the great producer would have sunk Notorious, we’ll never know. He did push hard for the unavailable Joseph Cotten instead, citing Grant’s “difficulty,” which seems to have really meant “high price tag.” Certainly, Cotten was terrific in his earlier work with Hitch, Shadow of a Doubt, but his screen chemistry with Bergman would prove dismal in the star-crossed Under Capricorn a few years later. In any event, an unexpected blessing to everyone but Selznick intervened: Duel in the Sun, which he seemed to think would be “Gone with the Wind II” and which everyone else called “Lust in the Dust” for years, featured his squeeze Jennifer Jones, who, like Selznick, was still married to someone else. The naturally fraught production consumed him, and he sold Notorious to RKO, resulting in a filmmaking team high on the sweet wind of freedom.

They created a masterpiece. Hitch and Hecht worked on the script and it’s lean and not too clean, with a rare ambiguity for Hollywood. And there’s a new kind of suspense; where Hitchcock used nerves and bombs in earlier movies (Blackmail, Sabotage), he here uses betrayal, distrust, and bitterness to keep the audience breathless. When Grant is forced into pimping out Bergman in the name of duty, the two convey more agony with silent glances than a decade of 70s method actors gnashing their teeth and bellowing.

Ted Tetziaff’s cinematography works nicely; the Hollywood vet and Carole Lombard favorite also shot My Man Godfrey. Following this picture, he’d become a director, with the noir pic The Window his most famous work. (Uncredited cameramen Gregg Toland and Robert Capa certainly helped.) Edith Head makes sure that everyone is dressed to, well, kill, and Theron Warth’s editing makes it all sing.

The whole thing is about as close as it gets to perfect. Arguably, there’s a tenderness here that Hitchcock would never again display. He’d make one more movie with Bergman, the experimental failure Under Capricorn; during and after, Bergman would “betray” everyone by running off to be with Roberto Rossellini. It would take Hitch five years to find another gorgeous blonde to crush on, and Grace Kelly never had the warmth or talent of Bergman. All the right things fell in place for Notorious, a rare and pure cinematic gem.

192. Great Expectations

Posted: July 23, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Alec Guinness, Alfred Junge, Bob Cracker, Cinema 1001, David Lean, Finlay Currie, Great Expectations, Guy Green, In Which We Serve, Jean Simmons, John Mills, Martita Hunt Leave a comment

The 1001 Book Why: Karen Krizanovich deems it “the finest literary adaptation ever filmed, as well as one of the best British films ever made,” and cites Oscars for Best Art Direction and BW Cinematography, with noms for Picture, Director, and Adapted Screenplay.

Where to Watch: Jump to the movie in its entirety on YouTube.

The Haiku:

Old Miss Havisham

Rasps out, “A great bride cake. Mine!”

Creepy delicious.

The 1001 Take: Seven of the BFI’s top 100 British films of all time are David Lean’s, more than any other director; this one is number five. But contrary to what many people think based on his later work, Lean is not necessarily about Technicolor spectacle sweeping across massive locations. Four of the seven movies are black and white beauties, and it’s hard to imagine his two Dickens-based works shot any other way.

It’s also hard to imagine anyone doing Dickens better within the confines of a two-hour feature; the multi-hour Nicholas Nickleby on stage and TV and the wonderful musical The Mystery of Edwin Drood pass muster, but they’re different formats. According to an interview conducted by the AFI (and contained in Conversations with the Great Moviemakers of Hollywood’s Golden Age, edited by George Stevens, Jr. source of all quotes contained here), Lean was initially daunted by the material and hired novelist Clement Dane, a “sort of” Dickens expert. “I think the thing not to try to do is a little bit of every scene in a novel, because it’s going to end up a mess,” he states. Dane’s screenplay did exactly that, and was rejected. Lean “got the book and quite blatantly wrote down the scenes that I thought would look wonderful on screen.”

The result is stunning, and the opening may be the most beautiful horror movie ever shot, as a child races under gibbets, empty ropes swinging, to a cemetery. There, young Pip (Anthony Wager) encounters the fierce Magwitch (Finlay Currie). Then things crank up to genius level when we enter the crumbling mansion belonging to Miss Havisham (Martita Hunt) and her protégé Estelle (Jean Simmons, a startling beauty), played by Martita Hunt. In this first act particularly, the casting is spectacular and so are the actors.

That Act II feels a bit of a letdown may be inevitable—and yet, its moderate tempo may be a needed respite given the speed and intensity of Act I, which will be back for Act III. John Mills was famously criticized as being too old—a 38-year-old playing 20-year-old Pip. While he’s solid and certainly less distracting than the AARP candidates in Grease, he and Valerie Hobson (grown-up Estelle) aren’t nearly as captivating as their younger counterparts. What energy there is stems from the one child, skinny John Forrest, who grows up to be Alec Guinness as Herbert Pocket. Lean said that Guinness was a nervous wreck in this, his first speaking role; the director would tell the actor that they were just rehearsing and roll film without Guinness knowing. To hear them tell it, neither was very fond of the other and they argued constantly. And yet Guinness kept coming back, and Lean kept getting spectacular work out of him in a partnership over five films, one of which would land Guinnes the Best Actor Oscar (Kwai).

With the return of Currie in the last third, and Hunt soon after, the movie starts clipping along again at its original pace; Dickens’ adaptations have to move fast to keep viewers from getting mired in the handy coincidences that drive them, and Lean knows it. The ending leaves you satisfied, and the overall experience is immersive, and feels like a thorough dunking in Dickens even with all the liberties taken. Lean would do a follow-up with Oliver Twist a few years later, Green behind the camera once again, and that version remains the best of the many attempts to condense that story into a performance.

Much of what makes GE work is its deep, dark, mysterious feel and the beautiful work of Guy Green, who had, up to that point, worked as a camera operator on the Lean film In Which We Serve. Lean had begun photography with Bob Cracker, but Lean claimed “it was almost the same as Brief Encounter, very real-looking.” He wanted “much more daring. Huge, great black shadows. Great big highlights over the top, because it’s Dickens.” Green stepped in and ended up winning the b/w cinematography Oscar for the year. The ghostly gray melts into black. In Miss Havisham’s, the atmosphere seems so tangible that you may have a physical reaction, reaching up to brush cobwebs out of your hair or grab for your stomach as rats scurry over the huge cake encrusted with mold.

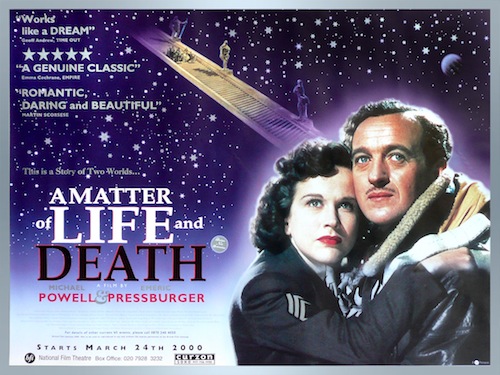

191. A Matter of Life and Death

Posted: July 22, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: A Matter of Life and Death, Alfred Junge, David Niven, Defending Your Life, Emeric Pressburger, Heaven Can Wait, It's a Wonderful Life, Jack Cardiff, Karen Krizanovich, Kim Hunter, Marius Goring, Michael Powell, posthumous reprieve, Reginald Mills, Stairway to Heaven, The Archers Leave a commentJump from this link to watch the movie in its entirety on YouTube.

The 1001 Book Why: Karen Krizanovich calls it “a lasting tale of romance and human goodness that is both visually exciting and verbally amusing,” and also gives a lot of love to Alfred Junge’s set design.

Where to Watch: YouTube, linked above.

The Haiku:

Long escalators.

Heaven’s a bureaucracy.

You might as well live.

The Cinema 1001 Take: The 1001 editors do love The Archers, aka Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, giving them two shoutouts in 1946 alone (Black Narcissus is on deck). It’s a delight. No one does intelligent romance like P&P.

As noted in the 1001 book and in any discussion of the movie, Matter was conceived as a propaganda film to ease strained relations between Britain and America post WWII. I didn’t know there were strained relations, but the Brits were not thrilled over America’s late entry into a war that had crushed the hell out of their country. Rather than focus on an American serviceman having his way with an English rose before disappearing, Matter flips the roles, beginning with a marvelous scene in which a British pilot (David Niven) leaps from his airplane, preferring that to literally going down in flames, as a helpless WAC (Kim Hunter) tries to talk him through it. (If this scene doesn’t call September 11 to mind, you must not be old enough to remember that day in 2001.)

From there, we’re transported to the terrifyingly efficient bureaucracy that is the movie’s Heaven—a grim place that nonetheless points up the distinction between Americans and Brits with fine humor. In a rare glitch, a death has been botched. Niven’s character is alive, in love with Hunter’s character, and louche angel Marius Goring has to un-botch if possible.

The idea of getting a posthumous reprieve was not new, of course; the first Heaven Can Wait had been made in 1943, and the concept is still popular today (Albert Brooks’ Defending Your Life is a relatively recent example). But this movie, and It’s a Wonderful Life (which would be released in the states within a month of Matter‘s British premiere) are both decidedly darker. It’s only natural that, with the boys safely, if not always soundly, home, what-if speculation would occur.

But unlike Wonderful Life, the reverence for celestial beings is absent from Matter. In fact, the point of view leans decidedly toward Niven’s character simply hallucinating as result of brain trauma as opposed to any actual intervention, a nice humanistic touch in contrast with the cosmic silliness of Wonderful Life‘s opening and closing bits. “We are starved for Technicolor in heaven,” quips Goring, as he witnesses the gray rose on his lapel morphing to a glorious pink. Indeed, the technical artistry and experimentation of Matter is one of the primary reasons to watch it. It’s hard to imagine an American director embracing a vision of Heaven as a monochromatic, rank and file/black and white environment with stairways straight out of Escher, as opposed to the vibrant richness of earth. No wonder Niven fights so hard to stick around. (The Archers were not pleased with the American retitling of “Stairway to Heaven,” but the original title was deemed too grim for Yanks.)

Jack Cardiff’s masterly cinematography and ease in both color formats does justice to Junge’s production design, and Reginald Mills’ editing—including incorporating freeze frames with motion, as well as b/w-to-color transitions—is seamless. Above all—or rather, beneath—is the superb writing of Powell and Pressburger. Yes, it’s formula, and yes, you know it will turn out all right; this is post WWII and no one wanted more heartbreak. But within that container, there’s suspense, wit, and agile, vigorous thinking that challenges without being abrasive. Anyone interested in filmmaking or good storytelling will benefit from studying The Archers, writers most of all.

190. The Killers

Posted: July 21, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Anthony Veiller, Ava Gardner, Burt Lancaster, Cinema 1001, Film Noir, Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Miklos Rosza, Quentin Tarantino, Robert Hilton, Robert Siodmak, The Killers 4 CommentsThe 1001 Book Why: Martin Rubin claims it’s superior noir, with a non-linear flashback that allows detective Edmund O’Brien to relive Burt Lancaster’s sexier life without suffering the consequences—just the vicarious thrill audiences get from watching crime movies.

How to Watch: The Criterion edition features the 1964 adaptation as well, and a bunch of cool extras, including an Andrei Tarkovsky student project that is a 19-minute version of the movie.

The Haiku:

Hemingway’s story

Rocks the first minutes so hard.

The rest is OK.

The Cinema 1001 Take: For those who take the side that Hemingway was a superb short story writer and a less satisfying (even lousy) novelist, The Killers provides strong evidence. The first twenty minutes of this movie, a faithful adaptation of the eponymous story, are so kickass, so scary, with two of the most frightening sociopathic criminals ever put on film—the suspense is painful. Surely every filmmaker who ever shot cold-blooded gangsters, particularly Scorsese and Coppola, has watched this a million times. It still feels completely modern, and it’s a gorgeous realization of one of Hemingway’s crystalline, hard-edged and brilliant stories.

And then….well, we’ve got another 80 minutes of screen time to fill.

The enigmatic beauty of the story—a guy simply waits until he’s violently killed—is lost when Hollywood, bless its heart, feels the need to explain why (and that, by the way, he kinda deserved it). Rubin’s points noted above—that the use of non-linear flashback and the meta aspect elevate the film somewhat—are well taken. But well-constructed and taut are hardly synonyms for the blow-the-bloody-doors-off greatness that is this movie’s beginning. The movie doesn’t plod, but chances of the explanation living up to that prologue are slim.

It’s Burt Lancaster’s debut and Ava Gardner’s breakout after 5 years of pretty girl tedium, and they’re both stunning to look at. The film was a critical and commercial hit, doubtless in no small part due to the two stars’ eye candy quotient, and it grabbed 3 Oscar noms, including director for Robert Siodmak, editing for Robert Hilton, adapted screenplay for Anthony Veiller, and the beautiful score by Miklos Rosza. It’s also one of those movies that film geeks revere. Watch it just in case you end up at a dinner party with Tarantino.

189. The Big Sleep

Posted: July 18, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: A Night at the Opera, Cinema 1001, Duck Soup, Howard Hawks, Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Martha Vickers, Raymond Chandler, The Big Sleep, To Have and Have Not 2 Comments

The 1001 Movies Book Why: According to Joshua Klein, “a noir masterpiece without several noir tenets” and a showpiece for Bogey as Marlowe.

The Haiku:

Bogey and Bacall

Talk sexy about horses

“Chinese”: code for “porn”

The Cinema 1001 Take:

“They sent me a wire … asking me, and dammit I didn’t know either.” That’s Raymond Chandler talking (source: Hiney, T. and MacShane, F. “The Raymond Chandler Papers”, Letter to Jamie Hamilton, 21 March 1949, page 105, Atlantic Monthly Press, 2000, according to Wikipedia), and the “they” is Howard Hawks and Humphrey Bogart. In fact, it’s a good thing that the movie rockets along on sexiness, because if you stop to try to figure it out, you’ll likely be as confused as everyone else. In fact, The Big Sleep is known as much for not making any sense as it is for being almost as high on the hot index as the previous Bogart/Bacall collaboration, To Have and Have Not.

Almost, but not quite. Where To Have‘s magic comes from its documenting two people falling in love, Sleep feels like work, which it was. Bacall apparently gave a nearly career-destroying performance in her second movie, Confidential Agent, and director Howard Hawks was instructed to patch things up by adding some scenes where she and Bogart could show they were still hot for each other, which at least wasn’t an act.

But between paring away other scenes to make room for the new ones—which had nothing to do with the story—and having to clean up Chandler’s seamier aspects to comply with the Hayes Code, it’s not wonder the movie’s a bit of a mess. Still, Hawkes, along with screenwriters William Falkner, Leigh Brackett, and Jules Furthman, did what he could to at least allude to the porn that is the main property sold at the bookstore featured early in the movie; note that Bacall’s onscreen sister, Carmen (Martha Vickers), is said to be “wearing a Chinese dress in a Chinese swing.” Ha! (The bookstore owner’s homosexuality didn’t have a shot at making it into the movie, but that was no doubt Hawks and Bogart’s machismo as much as Hayes.)

A brutal seaminess underlays the movie; in particular, Carmen is a disturbing character, and the youth of both Vickers and Bacall makes them seem especially vulnerable. At least, Bogart/Marlowe is there to look out for Bacall; there’s a distinct subtext that Vickers deserves whatever she gets. The experience of rewatching Sleep after seeing To Have for the first time as I followed list chronology reminded me very much of rewatching Night at the Opera after seeing Duck Soup for the first time. I had originally counted Sleep and Opera as favorite movies, but neither has the joie de vivre or untarnished thrill of their predecessors. Yes, everyone should watch all four. But for me, these prove that Sade song, “Never as Good as the First Time,” something I’ve only found sporadically true in the rest of life.

188. La Belle et la Bête

Posted: July 17, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Arakelian, Beauty and the Beast, Blood of a Poet, Christian Berard, George Auric, Jean Cocteau, Jean Marais, Josette Day, La Belle et La Bete, Lee Miller, Lucien Carre, Man Ray, Mira Parely, Nane Germon, Rene Moulaert Leave a commentThe Cinema 1001 Why: Joshua Klein states that the film reveals that, in Cocteau’s case, “poet” and “filmmaker” are not mutually exclusive. Additionally, a post-WWII directive to reposition the greatness of French filmmaking and Cocteau’s own drive to produce a mainstream work result in a finished product that holds up to this day.

The Haiku: [Leave one in comments. I’d love it.]

Where to Watch: The Criterion edition features a pristine transfer.

Look, the opening is a wee bit pretentious. But this is Cocteau. Blood of a Poet, his first work which features Man Ray’s muse Lee Miller, certainly wears that label with pride. That movie also pissed off surrealists, who labeled Cocteau a sell-out, and baffled pretty much everyone else. (Weirdly, it isn’t on the 1001 list.) Cocteau had plenty of marketing savvy, and chose to adapt a fairy tale, a French one at that and an inspired stroke.

After the opening sermonette, Belle kicks off with the great fun of Belle’s two sisters (Mira Parély and Nane Germon), who put on all sorts of silly airs and are ripe for some sort of reckoning. True, the period detail seems a bit literal for Cocteau. But the period he chooses—late 17th-century with plenty of silly headpieces and farthingales—has an undeniable lyrical flow in its look, and he makes the most of capes, billowy sleeves, ruffs, and corsets.

Cocteau uses George Auric’s score as if he’s staging a ballet; the music is perhaps most striking during the atmospheric tramp through the woods to the Beast’s house. The fantastic hallway, with human arms bearing candelabra, the human hands pouring wine, the statues with moving eyes—even decades later, it’s still magical, and handled with delicacy and exquisite grace. And when Belle floats through the castle in slo-mo, curtains wafting around her like ghost dancers, you may still feel your breath catch in your throat at the sheer beauty of it.

Cocteau seizes the sensuality of the good horror movies, particularly Tod Browning’s Dracula, and makes sure that every single component of the frame, from props to actors, is as exquisite as possible. Josette Day has a Vermeer-esque beauty, and, at the same time, a striking resemblance to Carole Lombard. Jean Marais appears three times, as the doomed suitor Avenant, then the Beast under a ton of padding and make-up (by Arakelian), and finally, of course, as the transformed prince. The Beast himself is marvelous, with a somber majesty. Marais’s characterization is regal and never silly; there is nothing cuddly about him, unlike the Disney beast that, like that studio’s movie, is so closely patterned on this original and yet so stuffed-animal/amusement park friendly.

There are plot holes, the ending’s confusing, and occasionally there are hard cuts to black cards that are a bit jarring, and almost seem as if Cocteau got bored or distracted and told editor Claude Ibéria, screw it, cut to black. But Cocteau and his small team of artists—including the production design and set decoration trio of Christian Bérard, Lucien Carré, and René Moulaert, costumes by Bérard, Antonio Castillo, and Marcel Escoffier, and photography by Henri Alékan—created a jewel that children, their parents, and the snobbiest cinephiles can appreciate with equal delight.